The gentle chime of a Victorian locket opening after decades of silence, the sudden fiery spark of light catching a cleaned Edwardian diamond – these are the moments that define the work of an antique jewelry conservator. Yet behind these moments of quiet triumph lies a complex and often contentious philosophical battlefield. The central question, one that has echoed through museum halls and private workshops for generations, remains deceptively simple: should we restore a piece to its original, gleaming glory, or preserve its accumulated history, patina and all? This is not merely a technical decision but a profound ethical dilemma, balancing historical integrity against aesthetic desire, and authenticity against functionality.

The philosophy of ‘restoration to original state’ is a powerful one. Its proponents argue that a piece of jewelry is, at its heart, a work of art and craftsmanship. Its true value and the intent of its creator are only fully realized when it appears as it did the day it left the master’s bench. A heavily tarnished silver necklace, they might say, obscures the intricate filigree work painstakingly executed by a 19th-century silversmith. The grime of ages filling the engraved lines of an Art Nouveau pendant masks the fluid, organic forms that are the very signature of the period. To leave it in such a state is to disrespect the artist’s vision. This approach often employs extensive cleaning, replacement of missing stones with perfect matches, and even the re-tipping of worn prongs or rebuilding of broken clasps to full strength. The goal is a seamless intervention, making the piece not only beautiful again but often wearable and secure for modern use. For a private collector who wishes to wear a beloved heirloom, this path can be incredibly appealing, transforming a fragile relic into a vibrant, functional object once more.

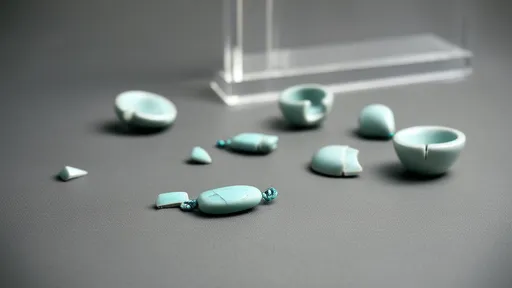

In stark opposition stands the principle of ‘conservation as preservation’, often summarized by the phrase “conserve not restore.” This school of thought, deeply influential in modern museum practice, treats every antique object first and foremost as a historical document. The wear on a ring’s shank tells a story of it being worn for a lifetime; the slight discoloration of a pearl suggests its age and organic nature; the unique patina on gold (a result of oils from human skin and exposure to air over decades) is seen not as dirt to be removed, but as a prized evidence of its journey through time. The conservator’s role here is to stabilize the object—to halt active deterioration like a cracking enamel or a loose stone—but to do so with absolute minimal intervention. Any new material added (like a solder join to repair a break) is deliberately slightly different in color or sheen, making the repair visible upon close inspection. This approach prioritizes the object’s authentic history over its aesthetic perfection, arguing that to erase all signs of age is to erase a fundamental part of its identity and story.

Navigating this ethical tightrope requires more than just technical skill; it demands a deep contextual understanding of each individual piece. A conservator must become a detective and a historian. The decision-making process is rarely black and white. For instance, a missing stone in a mass-produced Victorian mourning brooch might appropriately be replaced with a visually identical modern one to restore its completeness. However, replacing a missing stone in a one-of-a-kind piece by renowned Art Deco designer Suzanne Belperron would be a far graver ethical breach, potentially altering its very authenticity and astronomical value. In such cases, if the original stone cannot be found, the ethical choice might be to leave the setting empty, a silent testament to its history. Similarly, cleaning is a spectrum. Removing harmful corrosive compounds is essential for preservation, but aggressively polishing away all the nuanced patina on a ancient Roman gold ring would be seen as a destructive act, stripping it of its ancient character.

The very materials used in the process are subject to ethical scrutiny. Modern chemicals and aggressive polishing techniques can be unforgiving, potentially removing microns of valuable metal or altering the surface characteristics of gems. Conservators increasingly favor reversible methods—using stable, modern adhesives that can be dissolved later or making repairs that can be undone without damage by a future expert with better technology. This concept of reversibility is a cornerstone of modern conservation ethics. It acknowledges that our understanding and technology evolve, and we must not make permanent decisions that future generations may regret. It is an act of humility, recognizing that we are temporary stewards, not final arbiters, of an object’s long history.

Ultimately, the debate between ‘restore’ and ‘preserve’ is not about finding a single correct answer. It is about a mindful, respectful dialogue between the past and the present. The best conservators are those who listen intently to the story the jewelry itself tells—through its construction, its wear patterns, its damages, and its beauty. They weigh the desires of the current owner against their responsibility to the object’s long-term legacy. Whether the choice leans towards a sparkling renewal or a stabilized preservation, the guiding principle must always be a profound respect for the artifact’s integrity. The goal is never to deceive, but to honor. In doing so, we ensure that these exquisite fragments of history continue to tell their stories, in all their complex and layered glory, for generations yet to come.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025