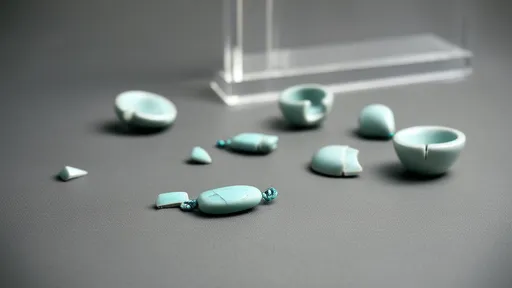

In the hushed halls of museums and the intimate spaces of private collections, a quiet but profound debate endures regarding the ethics of restoring antique jewelry. This is not merely a technical discussion of methods and materials, but a philosophical inquiry into the very soul of an object. Should a piece be returned to its original, gleaming glory, as if the centuries had never touched it? Or should the patina of age—the gentle wear, the minor imperfections, the subtle scars of a lived history—be preserved as an intrinsic part of its narrative? The answer is rarely straightforward, residing instead in a complex interplay of historical significance, cultural value, and intended purpose.

The argument for a comprehensive restoration, often termed a conservation-led restoration, is compelling. Proponents of this approach argue that the primary duty of a conservator or owner is to honor the original artisan's intent. A jeweler from the Georgian or Victorian era did not craft a piece with the expectation that it would one day be valued for its cracks, tarnish, or missing stones. They created it to be a perfect, dazzling expression of art and craftsmanship. To leave it in a state of disrepair could be seen as a disservice to that initial vision. A full restoration can reveal details obscured by grime and damage, allowing us to appreciate the piece as its first owner did. Furthermore, from a practical standpoint, certain types of damage, if left unaddressed, can lead to further deterioration. A weakened clasp, a stressed metal setting, or active corrosion are not just aesthetic issues; they are threats to the object's very survival. Intervention, in these cases, is an act of preservation, ensuring the piece can be handled, studied, and appreciated by future generations.

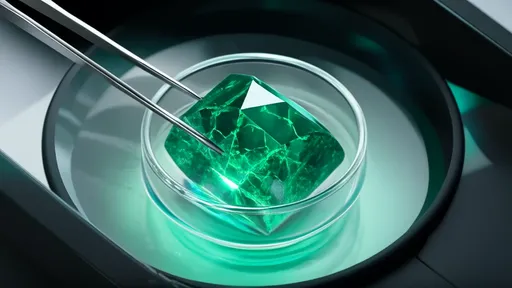

Conversely, a powerful school of thought champions the preservation of patina. This philosophy posits that the wear and tear on an object are not flaws to be erased but are chapters in its unique biography. Every tiny scratch, each softened edge, and the unique coloration of metal (known as its patina) tell a story. They speak of the piece being worn at a grand ball, passed down through a family, or surviving a tumultuous historical period. To polish away this history is to sanitize the object, stripping it of its authenticity and emotional resonance. In the world of art conservation, this is often described as the difference between restoration and conservation. Restoration seeks to return an object to a previous state, while conservation aims to stabilize its current state for the future, minimizing intervention. For many curators and collectors, this minimal intervention is the gold standard. It respects the object's entire life, acknowledging that its value is not frozen in the moment of its creation but has been accrued over time.

The decision-making process is rarely binary and is guided by a set of critical questions. What is the provenance and historical importance of the piece? A necklace owned by a queen might be treated differently than a charming but anonymous artisan's brooch. The former's historical value might demand a more conservative approach to preserve every physical clue to its past, while the latter might be a candidate for more extensive repair to return it to wearable condition. The intended future of the object is equally crucial. Is it destined for a museum display case, where it will be studied as a historical document? Here, preserving evidence of its age and use is paramount. Or is it a piece meant to be worn and enjoyed once more? In this case, structural integrity and aesthetic appeal might take precedence, though this can still be achieved with sensitivity to its age.

Modern ethical practices have therefore evolved towards a principle of reversibility and honesty. Any intervention should, whenever possible, be reversible. This means using materials and techniques that can be undone by future conservators who may have better methods or a different philosophical understanding. It also means that any new additions should be discernible upon close inspection to an expert eye. A replaced gemstone might be unmarked but documented, or a repaired clasp might use a slightly different alloy. This honesty prevents the creation of a forgery—a piece that misrepresents its own history. The goal is not to trick the viewer into believing the piece is untouched, but to extend its life while making its history legible.

Ultimately, the ethics of antique jewelry restoration exist in a delicate balance. It is a dialogue between the past and the present, between the hand of the original creator and the respectful touch of the modern conservator. There is no one-size-fits-all answer. The most ethical approach is one of deep consideration, where the unique story of each piece is listened to. The decision must weigh the object's physical needs against its historical soul, ensuring that whether it shines like new or shows the graceful marks of time, its enduring legacy is protected with wisdom and respect. This thoughtful stewardship guarantees that these beautiful relics continue to whisper their stories for centuries to come.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025