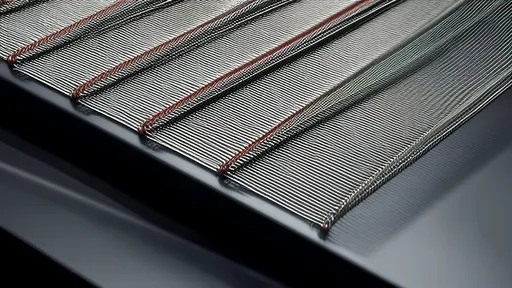

The delicate dance between softness and strength in 0.1mm gold wire represents one of material science’s most elegant challenges. For centuries, gold has been prized not only for its beauty and corrosion resistance but also for its malleability. Yet, when drawn into ultra-fine wires, the very properties that make gold so workable can become liabilities. How does one engineer a material that must be pliable enough to weave into intricate patterns yet robust enough to withstand mechanical stress without breaking? The answer lies not in the purity of the gold alone, but in a sophisticated interplay of metallurgy, mechanical processing, and microstructural design.

At the heart of this endeavor is an understanding of gold’s crystalline structure. Pure gold is a face-centered cubic (FCC) metal, which inherently allows for extensive plastic deformation. Dislocations—defects in the crystal lattice—move easily through the structure, granting the metal its characteristic softness. However, this same ease of dislocation movement means that pure gold wire is prone to necking and failure under tension. To imbue the wire with greater strength without completely sacrificing ductility, metallurgists introduce strategic impurities or employ severe plastic deformation techniques. Elements like silver, copper, or even minute amounts of rare earth metals can be alloyed with gold to create solid solution strengthening or precipitate hardening, pinning dislocations and increasing yield strength.

Yet, alloying is only part of the solution. The process of drawing the wire itself plays a critical role. As gold is drawn through progressively smaller dies, it undergoes work hardening—a phenomenon where dislocation density increases, making the metal harder and stronger but also more brittle. To counteract this, intermediate annealing steps are essential. By carefully controlling the temperature and duration of annealing, manufacturers can recover the microstructure, reducing dislocation density and restoring ductility without fully eliminating the strength gained from drawing. This cyclical process of deformation and annealing allows for the creation of a wire that is both strong and supple.

Recent advances have pushed the boundaries of what is possible with gold wire. Nanostructuring techniques, such as equal-channel angular pressing (ECAP) or high-pressure torsion, can produce ultrafine-grained or even nanocrystalline gold. These materials exhibit exceptional strength due to the Hall-Petch relationship, where smaller grain sizes impede dislocation motion. However, nanocrystalline metals often suffer from reduced ductility. Innovative approaches, like creating bimodal grain size distributions or introducing nanotwins, have emerged to overcome this trade-off. In a bimodal structure, coarse grains provide ductility while fine grains contribute strength, resulting in a material that enjoys the best of both worlds.

Another fascinating avenue of research involves the use of composite materials. By embedding nanoparticles or carbon nanotubes within the gold matrix, researchers can significantly enhance strength while maintaining, or in some cases even improving, flexibility. These reinforcements act as obstacles to dislocation movement, much like alloying elements, but often with greater efficiency and less impact on electrical conductivity—a valuable property in applications like electronics. The challenge lies in achieving uniform dispersion and strong interfacial bonding to prevent debonding under stress.

Beyond composition and processing, the very geometry of the wire can influence its mechanical behavior. For instance, a wire with a slightly oval or rectangular cross-section might exhibit different bending properties compared to a perfectly round one, depending on the application’s requirements. Surface finish also matters; a smooth, defect-free surface is less likely to develop stress concentrations that could lead to cracking. Advanced coating technologies, such as atomic layer deposition of protective layers, can further enhance durability without compromising flexibility.

The applications of such engineered gold wire are vast and varied. In the medical field, ultra-fine, strong-yet-flexible gold wires are used in implantable devices, such as neural electrodes or pacemaker leads, where reliability and biocompatibility are paramount. In luxury goods, they enable the creation of breathtakingly delicate jewelry that can endure daily wear. In electronics, they serve as reliable bonding wires in microchips, connecting dies to packages without failing under thermal cycling or mechanical shock. Each application demands a slightly different balance of properties, driving continuous innovation in how we process and design these tiny metallic threads.

Looking forward, the quest for the perfect gold wire is far from over. Emerging technologies like additive manufacturing offer new possibilities for creating graded or architectured materials with locally tailored properties. Computational materials science, powered by machine learning, accelerates the discovery of optimal alloys and processing parameters by predicting microstructural evolution and mechanical performance. As our understanding deepens at the atomic level, we move closer to a future where materials are not just chosen for their inherent traits but are designed from the ground up to meet exacting, even contradictory, demands.

In the end, the story of 0.1mm gold wire is a testament to human ingenuity—a reminder that even a metal as ancient and revered as gold still holds secrets waiting to be unlocked. Through a blend of ancient craftsmanship and cutting-edge science, we continue to weave strength and softness into every gleaming strand, transforming a humble wire into a marvel of modern engineering.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025