In the hushed stillness of the kiln, where fire and earth engage in their ancient dance, something extraordinary occurs—a phenomenon so elusive that it has captivated artisans and collectors for centuries. This is the world of ceramic firing, where the alchemy of flame, mineral, and chance conspires to create what is known as yao bian, or kiln transformation glazes. These are not mere colors applied by human hand; they are the kiln’s own whispered secrets, rendered in breathtaking, unrepeatable beauty.

The very essence of yao bian lies in its defiance of replication. Unlike controlled glazing techniques, where outcomes can be predicted and repeated, kiln transformation is a surrender to uncertainty. It begins with a carefully formulated glaze, rich in metallic oxides like copper, iron, or cobalt, brushed onto a bisque-fired vessel. But once the kiln door closes, control vanishes. The temperature fluctuations, the distribution of ash, the flow of oxygen, even the position of the piece within the chamber—all become variables in a complex equation with no fixed solution.

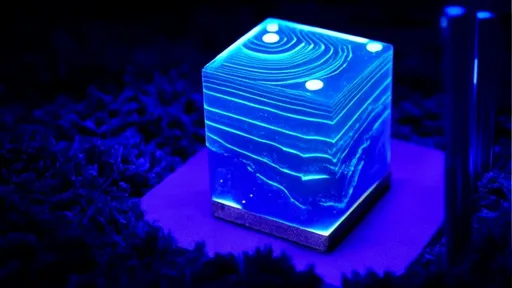

As the kiln climbs toward its peak temperature, often exceeding 1300 degrees Celsius, the glaze ingredients undergo dramatic transformations. Copper oxides might flux into swirling veins of crimson or emerald; iron can crystallize into rusty speckles or deep amber pools; cobalt might bleed into indigo waterfalls. The reduction atmosphere—a state of limited oxygen—can startle hues into existence that would never emerge in oxidation. It is a chaotic, beautiful disorder, a collaboration between the potter’s intention and the kiln’s caprice.

Historically, yao bian was often accidental, a happy flaw in the firing process that produced pieces so stunning they were regarded as divine gifts. During the Song Dynasty, Jun ware kilns in China became famed for their "sky-blue" and "lavender-purple" glazes, often streaked or splashed with rouge-like patches—the result of uncontrolled copper reduction. These pieces were so prized that they entered imperial collections, and kiln masters, though they tried, could never perfectly duplicate them. Each was a singular masterpiece, a fossilized moment of thermal serendipity.

Modern potters have embraced this unpredictability, not as a failure of control, but as a pursuit of higher artistry. They design glazes and kiln setups to encourage transformation—using wood ash accumulation in anagama kilns to create natural ash glazes, or employing soda firing to let sodium vapor dance with silica on clay surfaces. Yet even with advanced knowledge, the outcome remains gloriously uncertain. The potter becomes a guide, not a dictator, of the process.

Collectors and connoisseurs cherish yao bian pieces for their narrative quality. Each piece tells a story—of a specific firing, a unique thermal journey, a conversation between element and artisan. A vase might capture the flicker of a flame in a streak of gold; a bowl might hold the memory of a cooling crackle in its glaze network. This individuality stands in stark contrast to the uniformity of industrial ceramics, offering a tactile connection to the spontaneity of nature.

The emotional resonance of kiln transformation glazes extends beyond aesthetics. It speaks to a philosophical acceptance of imperfection and transience—a concept deeply rooted in East Asian traditions like wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in the imperfect, incomplete, and ephemeral. In a world increasingly driven by precision and duplication, yao bian is a testament to the romance of the unrepeatable, a celebration of the moment when science steps back and magic takes over.

Today, as ceramics enjoy a global renaissance, kiln transformation techniques are being explored and revered by artists worldwide. From the wood-fired kilns of Japan to experimental gas kilns in America, the quest for the accidental masterpiece continues. Workshops and kiln openings become events of anticipation, where artists and enthusiasts gather, breath held, to see what the fire has gifted them this time.

In the end, yao bian is more than a technique—it is a dialogue with uncertainty, a humble acknowledgment that some of the most beautiful things in life cannot be planned. They must be allowed to happen. In the marriage of flame and clay, we find a metaphor for creativity itself: sometimes, you must let go to discover something truly original. And in that discovery, we touch the sublime—the unrepeatable, fleeting, and utterly romantic art of kiln transformation.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025