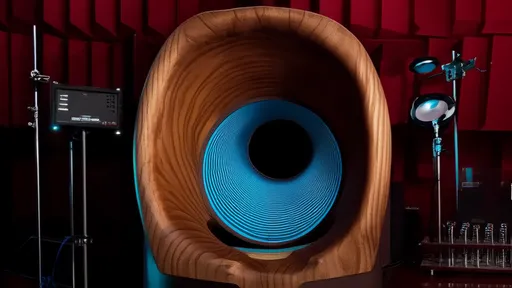

In the quiet corners of acoustic research, a fascinating phenomenon has captured the attention of scientists and musicians alike: the sonic amplification properties of wooden resonance chambers. Often overlooked in favor of their metallic or synthetic counterparts, these organic cavities are demonstrating extraordinary capabilities in sound enhancement that challenge conventional acoustic engineering principles.

The study, informally dubbed "Whispering Wood," explores how specific grain patterns, moisture content, and cellular structures within various wood types create unique harmonic profiles. Unlike manufactured materials, wood possesses inherent irregularities that, rather than diminishing acoustic performance, actually contribute to richer, more complex sound textures. Researchers have discovered that these natural variations act as microscopic sound diffusers, preventing the harsh standing waves that often plague perfectly symmetrical chambers.

Ancient instrument makers apparently understood these properties intuitively. The Stradivarius violins, renowned for their unparalleled sound quality, feature carefully selected spruce with precisely aligned annual rings that create what modern scientists call "directional resonance pathways." Contemporary analysis reveals that these instruments function not merely as sound boxes but as sophisticated acoustic filters that emphasize certain harmonic frequencies while suppressing others.

Modern applications extend far beyond musical instruments. Architectural acousticians are now incorporating wooden resonance chambers into performance spaces with remarkable results. The recently opened Harmonic Hall in Norway features ceiling panels made from specially treated pine that actively tune ambient sound. Rather than simply absorbing or reflecting noise, these wooden panels actually enhance desirable frequencies while reducing acoustic glare and echo.

The phenomenon appears particularly pronounced in hollowed tree trunks, which naturally form near-perfect resonance tubes. Field recordings taken inside ancient redwoods demonstrate amplification of specific frequencies by up to 12 decibels compared to open air measurements. This natural amplification occurs without the distortion typically associated with electronic sound reinforcement systems.

Perhaps most intriguing is the wood's memory effect. Repeated exposure to certain frequencies actually alters the cellular structure of the material over time, creating what researchers term "acoustic patina." This explains why older instruments often possess superior sound qualities that cannot be replicated in new constructions, regardless of craftsmanship. The wood essentially learns to resonate better with frequently produced tones.

Different wood species demonstrate distinct acoustic personalities. Maple provides bright, articulate amplification ideal for carrying melodic lines, while walnut offers warmer, more diffuse resonance perfect for supporting harmonic foundations. Cedar occupies a middle ground with exceptional responsiveness across frequency ranges, making it particularly valuable for full-range acoustic applications.

The moisture content within wood cells creates another layer of acoustic complexity. As humidity levels change, the expansion and contraction of cellular walls slightly alter resonance properties. This living quality means wooden chambers actively respond to environmental conditions, creating what acoustic engineers call "adaptive resonance." This natural responsiveness may explain why wooden performance spaces feel acoustically alive in ways that synthetic venues often lack.

Cutting techniques significantly impact acoustic performance. Quarter-sawn wood, where cuts are made radially from the center of the log, produces straighter grain patterns that conduct sound more efficiently than slab-cut alternatives. The angle at which wood is cut relative to its growth rings determines how vibrations travel through the material, affecting both amplification and tone coloration.

Researchers have developed computer models that simulate how sound waves interact with wood's complex internal structure. These models reveal that wood doesn't merely amplify sound—it transforms it. The cellular structure acts as a natural equalizer, enhancing mid-range frequencies that human ears find most pleasing while gently rolling off harsh high frequencies and muddy lows.

Practical applications continue to emerge beyond music and architecture. Medical researchers are experimenting with wooden stethoscopes that provide more nuanced acoustic information than plastic or metal versions. Automotive engineers are incorporating wooden elements into luxury car interiors to reduce road noise while maintaining acoustic clarity. Even smartphone manufacturers have filed patents for wooden resonance chambers to improve speaker quality without increasing device size.

The environmental implications are equally promising. As sustainable forestry practices improve, wood presents a renewable alternative to petroleum-based acoustic materials. Unlike synthetic foams and composites, wooden resonance chambers actually improve with age and can be easily recycled or biodegraded at end of life.

Future research directions include genetic mapping of trees with exceptional acoustic properties, development of wood hybridization techniques to enhance desired sonic characteristics, and creation of digital twins that can predict how wooden chambers will perform before physical construction begins. Some researchers are even exploring whether artificially accelerated aging processes can replicate the acoustic patina that normally develops over decades.

As science continues to unravel the mysteries of wooden resonance, one thing becomes increasingly clear: nature's oldest building material still has much to teach us about sound. In an increasingly digital world, the organic sophistication of wood reminds us that some of the most advanced technology grows on trees.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025