In the quiet corners of archaeology labs and the sterile halls of data centers, an unusual convergence is taking place. The ancient, tangible craft of metal preservation is finding common cause with the modern, abstract science of digital memory storage. This intersection forms the core of a fascinating field we might call "temporal safekeeping"—the art and science of creating time capsules not just for objects, but for information itself, ensuring both can speak to the future.

The challenge of preserving metal artifacts is as old as civilization. From the bronze statues of antiquity to the iron hulls of sunken warships, the enemy has always been the same: corrosion. This relentless process, a fundamental reaction of metal with its environment, is a battle fought on a molecular level. Traditional methods have involved creating physical barriers—oils, waxes, specialized coatings like the vivid verdigris on bronze—that shield the metal from moisture and oxygen. More advanced techniques, such as cathodic protection used on pipelines and ship hulls, turn the entire structure into a cathode in an electrochemical cell, effectively halting the corrosion process before it can begin. These are the well-honed tools for preserving our physical heritage, for ensuring a wrought-iron gate or a stainless-steel sculpture remains as its maker intended.

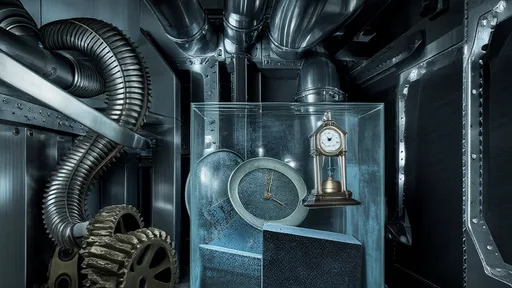

Yet, in our current era, we face a new kind of decay. Our most valuable artifacts are no longer solely forged from metal; they are sequences of ones and zeros, stored on media that are themselves vulnerable to physical degradation. This is the digital dark age, a paradox where we have produced more information than any civilization in history, but on formats with alarmingly short lifespans. Magnetic tapes lose their charge, optical discs delaminate, and solid-state drives have finite write cycles. The hardware and software needed to read them become obsolete within years, not centuries. The corrosion of bits is as real a threat as the rusting of iron.

The synergy between these two fields is where the concept of a true time capsule evolves. It's no longer sufficient to bury a sturdy box of stainless steel; we must also ensure the information inside remains retrievable and intact for centuries. This requires a dual-layer strategy. The first layer is the physical vessel. Here, metallurgy provides the answer. Using inert, highly stable alloys—perhaps titanium or specialized stainless steels—and protecting them with advanced, long-life coatings and controlled atmospheric environments (like argon gas fills), we can create a container nearly immune to time's physical ravages. This vessel must be a fortress, a hermetically sealed guardian against humidity, temperature fluctuations, and physical pressure.

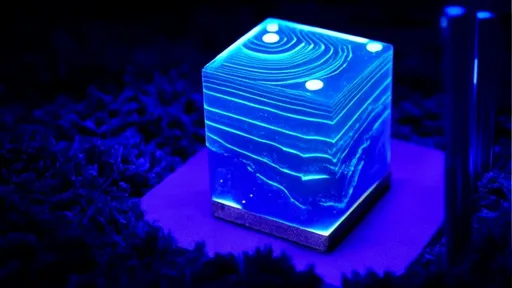

The second, more complex layer is the preservation of the memory within. This is where data science borrows a page from metal conservation's playbook: the principle of inertia and stability. Just as we seek the most stable, non-reactive metals for the capsule, we must seek the most stable, non-proprietary, and simple data formats for the information. Think engraved silica glass with femtosecond lasers, or analog optical etchings on durable metal foil—formats that require no complex software or hardware to decode, only light and a basic lens. The goal is to reduce the data to its most fundamental, physical representation, making it as permanent and readable as the engraved text on a bronze plaque.

Looking forward, the research is pushing into even more profound territory. Scientists are experimenting with DNA data storage, encoding digital information into the sequences of synthetic DNA, a medium with a proven half-life of centuries under the right conditions. The preservation challenge then mirrors that of biological samples, requiring stable, temperature-controlled metal capsules to house them. In another cutting-edge approach, researchers are developing nano-scale etching techniques on ultra-stable metal alloys, creating "Rosetta Stones" for the future that could store vast libraries of human knowledge in a space no larger than a coin, designed to last for millennia.

This fusion of material science and information technology is more than a technical exercise; it is a profound philosophical undertaking. It forces us to ask: What is worth saving? How do we communicate across vast gulfs of time to a future that may not share our languages, our cultures, or our technologies? The time capsule, therefore, becomes an exercise in universal communication. The metals we choose and the way we protect them must tell a story of permanence and intention. The data formats we select must be elegantly simple, relying on fundamental principles of mathematics and physics that are unlikely to ever become "obsolete."

Ultimately, the mission of preserving metal and preserving memory are one and the same. Both are a defiant stand against the entropy that seeks to erase all things. They are a promise made to the future, a declaration that our stories, our art, our knowledge—the very essence of our era—is worth remembering. By marrying the enduring strength of perfected metals with the timeless simplicity of wisely encoded data, we are not just building containers; we are building bridges across time, ensuring that however the world may change, a whisper of who we were will always remain.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025